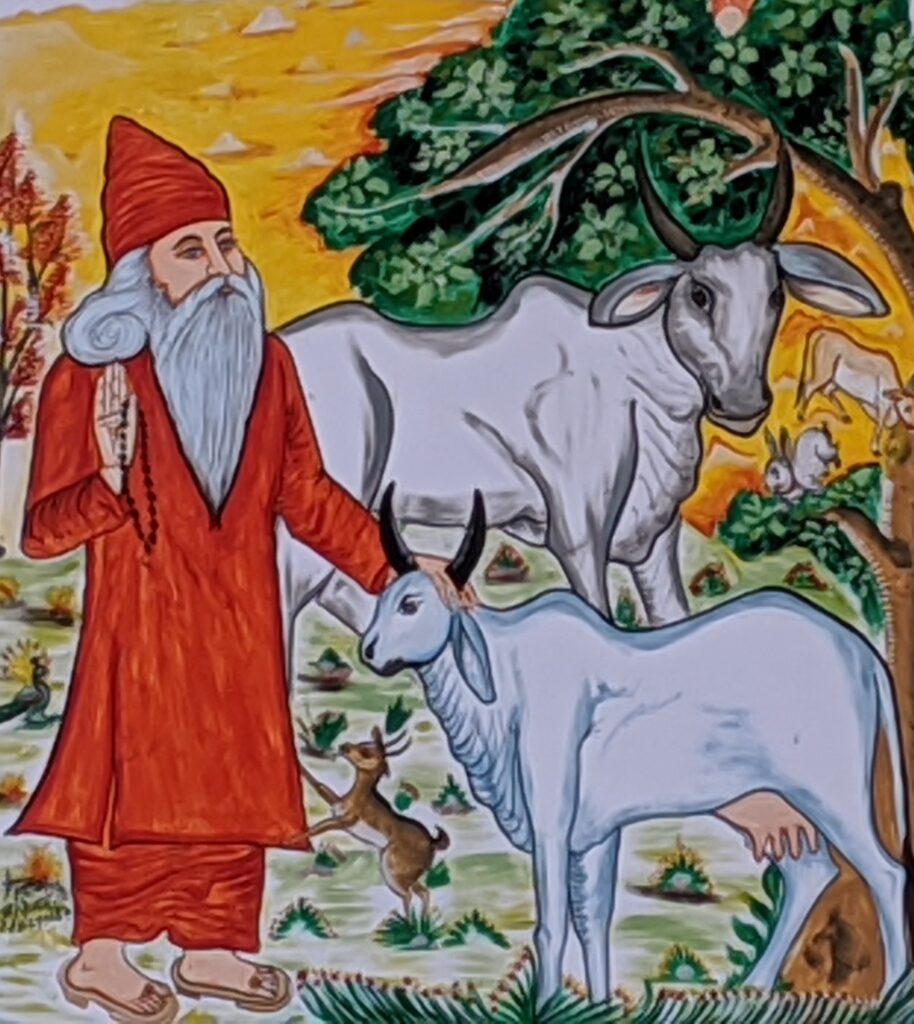

A ‘miracle’ story about Guru Jambhoji

(The setting: Lohawat is a village in the Thar Desert northwest of the city of Jodhpur. Businesses that line the road, such as a garage and motorcycle sales office, carry the name of Guru Jambheshwar – the more formal name of the Bishnoi’s founding guru Jambhoji. The guru’s father, Lohat, is said to have come from this village. The Bishnois have set up a sanctuary on the outskirts of the village, which cares for wounded animals before returning them to the wild. Heading out from town you reach the statue to the late 20th century Bishnoi martyr Birbal Bishnoi, killed while defending gazelles from poachers [his story and those of others from the village are told in My Head for a Tree]. In honour of Birbal, the surrounding land was given official conservation status. On my visit in 2020 it the land was filled with grazing chinkara, a graceful gazelle. In 2022 there were none, most likely due to attacks from feral dogs which frighten wildlife from homesteads around which these dogs congregate. Birbal’s statue faces a road leading up a hill, a compacted sand dune, which holds the Bishnoi temple where this story unfolds.)

Let me introduce a young Bishnoi priest: Swami Aatmanand Ji Maharaj Lohawat . At just fourteen years old the words of Guru Jambhoji, the 15th century founder of his religion, pulled him toward the temple at Lohawat where he became a disciple of the resident priest. There are no training schools for Bishnoi priests: discipleship is the route towards priesthood. You learn to lead the services, study the sacred texts, and offer support and spiritual guidance to your community. When your priest decides you are ripe for ordination, you travel to the Bishnoi temple at Jambha.

For regular followers, the lead temple is seen as being Mukam, where Guru Jambhoji is buried. For priests, it is the temple at Jambha. Inside the town of Jambha is a residential block akin to a monastery, where I once ate inside a cloister alongside a flurry of hungry, youngish men in saffron robes. When a disciple is being elevated to priesthood he comes here, he calls existent priests to a feast he provides, introduces himself, and offers himself in service. There are two levels of priests: sants (curiously translated into English as ‘saints’), and senior to them, mohants.

This priest, Swami Aatmanand, aged about thirty, assumed authority of this temple when its priest, his mentor, died two years before. That was in 2020, when I had last visited this hilltop site. Since then a whole new sathri, a pilgrimage house, has been built from pink stone. Sixteen of these sathris exist, built in places where Guru Jambhoji settled and taught for a time. This one is broad, with delicate carved columns, set back behind a deep courtyard of red sand, surrounded by a high fence. The priest came out through its gate to meet us.

His lunghi and overshirt were well-pressed, a scarf of lighter saffron draped over his left shoulder, and a string of orange beads hung around the open neck of his top. He is tall, his hair full and black, his beard trimmed, his nose aquiline, his gaze returning toward the distance even when talking to you. Such a good-looking man could stir excitement if he chose, but his is a celibate order and his movements are quiet, his presence serene. Does he notice young people, affected by climate change, growing more anxious?

‘No,’ was his simple response.

On my previous visit to this hill I encountered a flock of wild chinkara. Their heads were the height of my chest, and they approached warily, shivers of fear passing up from their necks to their ears, bowing their heads to show me their ridged horns, dancing backward on spindly legs. Today there are no such gazelles, just us people, but multiple acres of the desert plain below are surrounded by high red walls. A high formal entrance gate suggested that this was to an exclusive gated housing development. In a way it is, but the residents will be chinkara. This is to be a wildlife reserve where the chinkara are protected from roaming dogs. Businessmen in the village told funds were raised and the sanctuary was being built at the young priest’s suggestion. Swami Aatmanand clearly has power within his community.

He moves to the shade of a tree and shifts into storytelling mode. People have told me that Jambhoji’s teachings cannot be linked to the places where he delivered them, but much Bishnoi lore seems to be oral and localized.

In 1509 Jambhoji spent six months here. A principal character in the priest’s first story is the ruler of Jaisalmer, so I’ll introduce him with an earlier tale.

The ruler of Jaiasalmer, Rawal Jait Singh, was in the company of a prince and visiting the nearby city of Osian. His leprosy was advanced. The two men turned their noses northwest. A fragrance touched them. It was faint, for it had travelled forty-five kilometres, a strong, unique scent they recognized as Jambhoji’s. They took to the road and followed it, climbing to where Jambhoji had taken residence on the Lohawat dune.

‘You’ve come a long way,’ Jambhoji said in greeting. ‘Let me feed you.’

The two men laughed. ‘Look at the size of our army, and all our vast retinue,’ the men said. ‘And we are used to dining off vessels made of gold.’ Perhaps the guru would like to join them?

But Jambhoji’s was not an idle invitation. He raised a hand and pointed to a distant dune. On its flank grew a tree.

‘Go to that tree’, he instructed two of his followers, ‘and dig a hole by its side.’

They did so, and soon their spades met the hardness of metal. They pulled the sand away with their hands and uncovered plates and drinking vessels all made of gold.

The men ferried the treasures back to the group, for whom food had meanwhile been prepared. A portion was placed on one of the gold plates and handed to the Rawal. He gathered the first mouthful between his fingers and pushed it between his lips. The meal was of vegetables, and it was as though the forces of life that powered growth inside the vegetables now powered through him. He took hold of his next mouthful. His fingers moved easily as he pinched at the food, and his lips opened without that sense of chapped soreness. The prince, his companion, left his own meal and stared at the Rawal. The signs of leprosy were gone.

‘How could this be?’ he asked. The food tasted no different to what they ate all the time, yet this meal had had such a profound effect of healing.

[In response, Jambhoji spoke the words since gathered as teaching numbered 94, in the collection of Guru Jambhoji’s teachiongs known as the Shabads. And to the Rawal, Jambhoji spoke words that were collected as Shabad 105.]

The meal was done, the gold plates and tumblers were cleaned, and Jambhoji instructed the two disciples who had dug them out from beside the tree were to now return them, hiding them once again beneath the sand. The followers did as told.

Well, almost.

The royal party had been so large, they had found so many gold plates. They selected two and buried them beneath a different tree. Later they could reclaim them and their families would be rich from their sale.

What might they do with such riches? Perhaps move to a different area where none would know them and question their sudden wealth. They could buy new land to pass to their offspring, their families growing larger with each generation.

Jambhoji of course knew, perhaps even before they had done so, that the men were stealing the gold plates. Actions, good and bad, have consequences. The disciples lusted after one future, but their acts of deception and theft committed them to another.

‘You will stay in this district of Lohawat all your life,’ Jambhoji informed them. ‘Your family will remain here, but it will not prosper and grow.’

Bishnoi families trace their lineage back through centuries to the time of Jambhoji.

‘The family is still here,’ the young priest told us, rounding off his tale. ‘And to this day, that family has very few members.’

The temple, a simple white building dating back 350 years, is sited a little way down the side of the hill. Beyond it are steps leading down to an occasional pond. In Jambhoji’s day there was a well here, but it attracted bands of dacoits who stationed themselves here and terrorized the neighbourhood, and so the local community filled it in.

Treading gently in his brown leather sandals, the priest led us into the courtyard where he opened the door to a central shrine. Inside is a print of Jambhoji’s left foot, embedded in stone. The priest stroked it softly. Every morning they wash it, he said, which is why it is fading away.

The Queen of Lalasar once came here, he told us. She was looking to become pregnant. After drinking water from this imprint of Jambhoji’s foot she conceived a baby boy and paid for the building of the temple in gratitude.

The story of the Queen of Lalasar and her yearning for a baby is told differently in the temple at Lalasar. She went there, prayed to Jambhoji, and promised to pay for the creation of a pond if her wish for a child was granted. When the baby was born she forgot her promise. At thirteen her young son died. Taking this as judgment for not having fulfilled her pledge, the queen sold all her belongings and donated the proceeds to the temple. They were used to build a pond.

Two different stories. ‘Which one is true? I asked the young priest at Lohawat.

‘I believe this one,’ he said.

(And indeed both could be true: the Queen drank from Jambhoji’s footprint at Lohawat, and honoured her promise to fund a new temple there, but forgot her pledge elsewhere that she would build a pond. She had spoken falsely. Her action had consequences.)

What is the young priest’s message for the world?

He thought for a while. ‘Follow Jambhoji’s teachings,’ he said. ‘Do so for generation after generation, and the world will be a beautiful place to live.’

[For more on the Bishnois, please read my MY HEAD FOR A TREE (here’s a review)